Earlier this term, I wrote about the value of a good chart writer in regards to having Lauren’s assistance at the Church Women’s United retreat, now the tables have turned and I can speak to it from the chart writer’s perspective. Although I took a lead in case development and agenda design, I specifically requested to not take a lead with facilitation as I wanted the opportunity to both observe someone else’s style and to be in the assistant role, something I’ve done surprisingly little of given my jump into the deep end of facilitating and teaching solo.

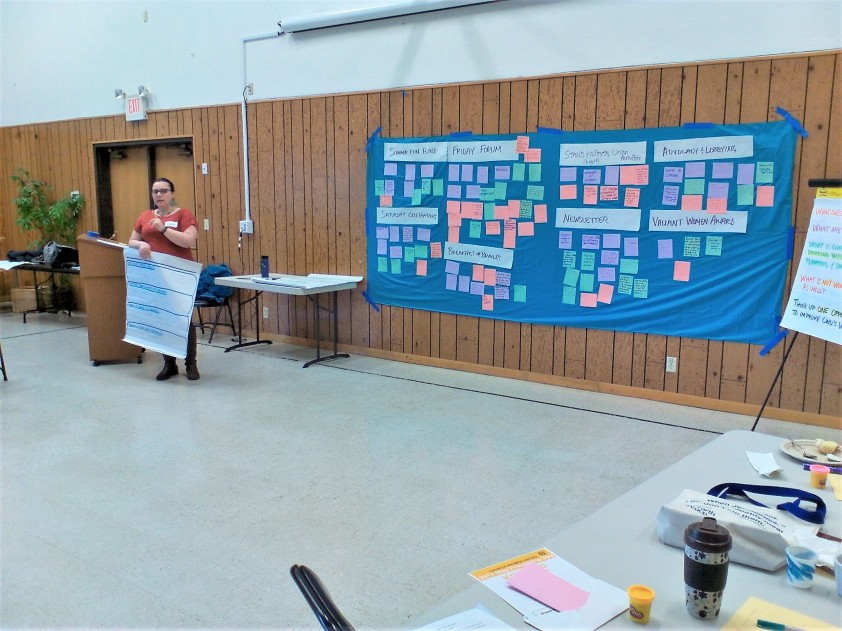

Well chart writing is thus what I signed-up for, and chart writing is what I did! Over the course of seven hours, I chart wrote 35 sheets, which when transcribed equated to more than 10 pages single-space, size 11 font. I’m taking it as a mark of honor that I not only went through an entire pad of chart paper, but that I also wore out the four main colors from a brand new set of Mr Sketch markers. At one point in time, I was tracking no less than four different topics—adding notes and symbols to charts lining the walls, easel and even some on the floor. Honestly, being able to track and record a complex dialogue of 40+ people is in the top three facilitation experiences of my young career.

There are a number of reasons that chart writing is so important. First and foremost, it is a visual and physical way for people to know that they have been heard. This is why it is so important to use bits and pieces of people’s own language when recording their thoughts. To quickly reference back to ye olde brain science, seeing your own words up in writing helps to calm the sympathetic nervous system which cues our “fight and flight” responses, with that system calmed our parasympathetic nervous system can rise to the service and let us “rest and digest.” Whether helping a group to heal or to make decisions (or both), participants are much more likely to find common ground if they can tune into their parasympathetic nervous system. Of course, if you misunderstand their intention, they also see that lack of understanding in big, fat permanent marker too.

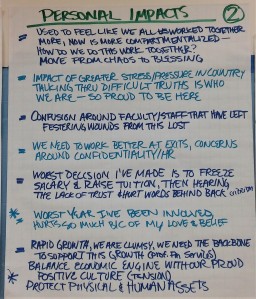

Over the course of the process, I saw both of these responses take place. First, I had multiple people come up to me during the breaks and tell me not only how impressive it was to watch me speed writing, but more that they didn’t realize how important what they had to say was until they saw it written before everyone else. This was especially true for two different contingencies around the narrative of “having to do it”: seeing that narrative written so explicitly provided opportunity for the sense of trauma to be recognized, while also opening the door to question if this is the type of organizational culture and spirit that they want to now perpetuate. I also saw someone who got more flustered with her words on the paper. In capturing one of the thoughts she voiced to the group, I jotted down: “we need to not be afraid of asking tough questions.” Which received wide agreement among the group. This frustrated her and she eventually sent me up a hand-written note that said: “Not being willing to ask certain questions and give the space to really look at these.” I’m ashamed to say that I still don’t know what the difference was for her, my only guess is that her emphasis was on the second part of the comment. Regardless of my ignorance, as soon as I wrote this exact sentence on the observations sheet, her entire presence shifted to one of openness and engagement with the process—she, at last, felt heard.

Finally, the second major value of chart writing is the creation of a group memory that outlasts the individual event. As previously mentioned, when transcribed my charts became over 10 pages of notes which formed the backbone of a report we created memorializing the event. Even with 40+ people in the space, there was at least a dozen others who really should have been there. Being able to provide a detailed and organized report with the voices of the participants provided the school with a way to help “bring along” those who were not present in body, as well as a launching pad to move forward generated ideas.

This past weekend I facilitated a three-hour retreat for the Church Women United (CWU), which is an inter-faith group of women who represent numerous churches in the Eugene/Springfield area. The group has been facing issues of leadership burn-out and difficulty with membership recruitment, especially engaging younger women of faith. To help them with these issues, I designed a retreat that would encourage the members to openly confront these issues that they had been avoiding. Specifically, we developed four objectives for the retreat: 1. Revitalize energy within the group, 2. Explore individual member’s motivations for involvement, 3. Identify current strengths & challenges of CWU activities, and 4. Develop strategies for membership & leadership capacity.

This past weekend I facilitated a three-hour retreat for the Church Women United (CWU), which is an inter-faith group of women who represent numerous churches in the Eugene/Springfield area. The group has been facing issues of leadership burn-out and difficulty with membership recruitment, especially engaging younger women of faith. To help them with these issues, I designed a retreat that would encourage the members to openly confront these issues that they had been avoiding. Specifically, we developed four objectives for the retreat: 1. Revitalize energy within the group, 2. Explore individual member’s motivations for involvement, 3. Identify current strengths & challenges of CWU activities, and 4. Develop strategies for membership & leadership capacity.